My first official conference talk in San Francisco went well.1 All of my words came out, I didn’t die, and I had a lot of really interesting conversations with smart people about mobile development and user experiences. On top of that, I got to meet actual people who have read my book, which is always a thrill. Most importantly, I did my best to accept encouragement or compliments at face value. This is very hard for me because of a disorder that I have named SCS.

SCS, as you may or may not know, stands for “Slow Clap Syndrome”, and it is surprisingly rarely diagnosed in the medical community. SCS is very simple, though. Whenever I get a compliment or encouragement, I automatically imagine a slow clap accompanying it in the background. Obviously this is just in my head, but it effectively negates the compliment unless I can think ahead to shut it off. It can be a sarcastic and condescending slow clap:

“I really (slow clap) loved (slow clap) your last blog (slow clap) article. It was sooo (slow clap) original.”

Or it can be the genuine, heartfelt slow clap you reserve for the art of five-year-olds you’re not directly related to and adults who have no idea they’re operating way out of their realm:

“Did you draw that pipe in Illustrator (slow clap) by yourself (slow clap)? It’s very good (for a five-year-old or an adult with a tragic but preventable head injury).”

What does this have to do with Father’s Day? My parents obviously didn’t give me a sarcastic slow clap, and they never patronized me. My father, possibly the most gifted musician that I have ever known, always encouraged me in piano, cello, bass, guitar, and anything else that I tried. He told me when I did well in a piano concert, and he informed me, bluntly, when I needed to practice more. Because I grew up with their honesty, my parents’ words always bypassed the “slow clap filter”. Slow claps were never added in post-production, and I took their words at face value.

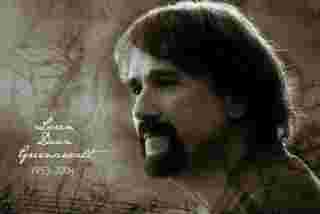

As a natural entertainer, my dad could always captivate a crowd. My dad died at the end of 2008, but I know he was proud of me. I know he would have loved seeing me give my first public talk in San Francisco, and he would have been following the whole thing on Facebook (once I persuaded him not to fly out). Most importantly, though, I know he would have been honest with me, and I could have heard everything he said without slow clap accompaniment. That’s what made him such a great dad, and that’s why, no matter what happened between us over the years, I can spend my Father’s Day remembering every nice thing he ever said and imagining how much fun we would have had hanging out on the back porch with some beers, good music, and stories of San Francisco.